Calm the Hell Down: AI is Just Software that Learns by Example and No, It’s Not Going to Kill Us All

Feel like watching or listening instead? Scroll to the bottom to watch.

Introduction

It’s June 2022. Google engineer Blake Lemoine tells the world that Google’s LaMDA has achieved consciousness. What started as a mere chatbot, he tells his bosses, is now sentient. Most people roll their eyes and wonder how someone with a Ph.D. in computer science can be so easily duped. Seventeen months later OpenAI releases ChatGPT and the world loses its mind. Artificial intelligence, whatever the hell that is, has apparently arrived.

Before we dive into this madness in hopes of retrieving sanity I’m just going to cut to the chase and tell you what AI is. It’s strikingly simple. AI is…wait for it…software that learns by example. Yes, that’s it. Let me explain what I mean.

You know what software is. You use it all the time. Gmail is software. Your Netflix app is software. The website you only go to when in Incognito mode? Software.

And you know what it means to learn by example. Kids do it all the time. They see examples of the word ‘the’ and then they can recognize it in a sentence. They see examples of what pigs look like and then they can point them out in the pictures of farm animals. You’ve seen examples of impressionist paintings and can now (more or less) point out which paintings in a gallery are impressionist. And so on. The notion of learning by example is well understood.

AI is software that learns by example. If you want your AI-enabled photo software to recognize when you take a picture of your dog then give it a bunch of photos of Pepe and it will “see” Pepe in new photos. If you want it to approve and deny mortgage applications, give it a bunch of examples of approved and denied mortgage applications and it can spot the ones that should be approved when you give it new applications. And if you want your AI to spot whether a bone is broken in X-rays, give it a bunch of examples of broken and unbroken bones in X-rays and it will get good at that, too.

You’re probably familiar with at least some of those examples. The one you’re definitely familiar with is AI that generates text, the most famous one being ChatGPT. That, too, is software that learns by example. ChatGPT and its ilk are quite good at stringing words together coherently because the software was given tons and tons of examples of words being strung together coherently.

For example, if someone tells you they have an AI that can talk to patients for therapeutic purposes, you now know that they must have given that AI a bunch of examples of words being strung together coherently that deal with, say, grief, loss, and depression. That’s why, when you say to the AI, “I’m feeling really lost, now that my mom is gone” it may reply with something like, “That sounds really hard” and not something that would be utterly incoherent like, “The frog ate my baby.” That’s just not even close to the sort of thing it saw in those examples that dealt with grief and loss.

Similarly, if someone tells you they have an AI that talks about the destruction of humankind, you now know that they must have given that AI a bunch of examples of words being strung together coherently that deal with, say, destruction, death, and murder.

Finally, if someone – like OpenAI, the creators of ChatGPT - tells you an AI can be engaged with to talk about either the loss of your mother or the destruction of humankind, you now know that it was given words strung together coherently about death in the context of losing a loved one and death in the context of an existential crisis for humankind. The same goes for any other kind of conversation you might have with an AI.

Now you’ve learned that AI is software that learns by example by virtue of being given a bunch of examples. It really is, in essence, that simple.

Sounding Fancy

It's going to be very important that we don’t let people push us around with big, fancy words when they talk about AI. That’s the kind of thing that leads us to walk away, assuming that AI is too technical, too complicated, for the layperson to understand let alone have an opinion about. Perhaps too complicated for politicians to address with effective laws and regulations. But a lot of people – especially technologists – do talk in this intimidating way. They may not intend to intimidate, of course. They might just be bad communicators to laypeople about their work, a disease that afflicts most specialists. But that way of communicating has a chilling effect all the same, and we can’t let that happen.

Let me show you what I mean by people talking with fancy AI words when they don’t have to.

“Software that learns by example” is a very non-technical way of putting things. If you’d like to sound technical, you can use a fancy word for ‘example’: you can say ‘data’.

Here’s a lowbrow question you can ask someone who is telling you about the AI they created: “What examples did you use to teach your AI?” Here’s the same question but now it’s highbrow: “What data did you use to teach your AI?” And if you really want to raise your brow, ask: “What training data did you use to train your AI?” The highbrow questions are fancy, but they’re asking exactly the same thing as the lowbrow question.

That said, there is obviously a lot you don’t understand at this point. There are different ways of getting AI to learn (e.g. supervised and unsupervised learning), there’s the math that underlies that learning (algorithms galore!), there’s the hardware required to learn in certain ways (about which Nvidia, maker of chips, is very happy about).But honestly, unless you’re really going to get into the deep, thick weeds of AI, you don’t need to go there. You also don’t need to throw around terms like “artificial neural network” and “deep learning.” If someone throws those words at you and you’re not an academic, a student, an engineer, or a data scientist, they’re probably just trying to showcase their own alleged knowledge in an intimidating way. Don’t let them push you around; they’re just talking about software that learns by example.

I want to speak plainly about AI – in a way that I hope most anyone can understand – because there are some very high stakes issues on the table. Literally life and death. And technologists and others are making some rather bold claims, including those about creating superintelligences and the potential destruction of humankind. If we’re going to soberly address their alarming claims, we can’t stumble out of the gate by drowning in a sea of irrelevant jargon. In this chapter, we’re going to tackle the boldest claim of all: that companies like OpenAI have created, or at least are in the process of creating, a new kind of intelligent entity.

One caveat before proceeding. I’m going to refer to “the technologists” as the ones making the bold claims. That’s not totally fair, since lots of technologists, perhaps even most, don’t buy the bold claims. And some of the people that do buy the bold claims aren’t technologists. But we have to call them something and this is the best I could do. Perhaps an AI could have thought of something better, but I’ll never ask.

The Good, the Bad, and the General

AI is software that learns by example (have I stressed this enough?). Once you know that, you have a great deal of insight into how things might go well or poorly for an AI.

If you give an AI bad examples, you’ll get a bad – that is, defective – AI. If you give it great examples, you’ll get a good – that is, functional – AI.

If, for example, all the examples of your dog are highly pixelated photos of him from only one angle in poor lighting conditions, it’s going to be very bad at recognizing Pepe in photos. You need to give lots of examples: different lighting conditions, different angles, his eyes open, his eyes closed, running, laying down, and so on. All else equal, the more examples you give, the better. Same with X-rays and words being strung together coherently: bad examples = defective AI, good examples = functional AI. (Fancy translation: if your training data is not sufficiently representative of the array of contexts in which the AI will be deployed, your AI will output too many false positives and/or false negatives, or incoherent text or really bizarre images, to be functional for the intended use-case).

OpenAI trained ChatGPT with a lot of examples of words being strung together coherently. Their examples included books, newspaper and magazine articles, blog posts, Reddit posts, and more. As a result, it got quite good at stringing words together coherently. So good, in fact, that a number of technologists have decided that what we have on our hands is at least the beginning of “Artificial General Intelligence,” or AGI. That term refers to an AI that manifests something like human level or even superhuman level intelligence; something between a 5-year-old human and an all knowing and wise oracle. It’s AGI that Blake Lemoine claimed to see and it’s the kind of AI technologists at companies like Microsoft, Google, and OpenAI are telling us is already here.

For instance, former Princeton professor of computer science and now Senior Principal Research Manager at Microsoft Research published a paper with his team in April 2023 titled, “Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4.“Given the breadth and depth of GPT-4's capabilities,” the researchers assert, “we believe that it could reasonably be viewed as an early (yet still incomplete) version of an artificial general intelligence (AGI) system.”

A vice president and fellow at Google research, Blaise Agüera y Arcas, along with Peter Norvig, a computer scientist at the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI, wrote in October of 2023 that “today’s frontier models [referring to the latest in AI text generation] perform competently even on novel tasks they were not trained for, crossing a threshold that previous generations of AI and supervised deep learning systems never managed. Decades from now, they will be recognized as the first true examples of AGI.”

And to cap off a year of bold proclamations, in December of 2023 OpenAI tells us that “Superintelligence could arrive within the next 10 years.”

Hearing these claims, it’s almost impossible not to think of The Terminator or Hal from 2001: A Space Odyssey. It all sounds very, very ominous. And to be clear, I doubt that these technologists believe that superintelligence entails evil beings bent on destroying or enslaving the human species. But still, since the language they use is so closely bound up with Hollywood-fueled human imagination, it’s worth our time trying to figure out whether what they’re saying is true. Are we really dealing with a new kind of intelligence? Might a superintelligence not be born but, rather, designed and created?

I greet these claims with a great deal of incredulity. The skepticism is not borne of a lack of confidence in their technical abilities; I’m sure those are vast and deep. Instead, the skepticism is the result of knowing a whole lot more than them about the philosophical underpinnings of their claims. This sounds pretentious, but in my defense, I was a philosophy professor for 10 years and a philosophy student for 10 years before that; if I don’t know more about philosophy than them, I must have been really bad at my job. Possible, yes, but not probable.

Burning Desire

We can begin to breathe a sigh of relief in reply to claims of superintelligence (and the scary images they conjure) by making two points of clarification. Let’s start by granting, for the sake of argument, that this software that learns by example is intelligent. (It’s not, but let’s give it to them for now). But granting that is not at all to grant that the software that learns by example is conscious or sentient.

To be conscious or sentient is to be capable of having experiences. In the words of philosopher Thomas Nagel, there is something it is like to smell a rose or taste a snail or feel nauseous or feel love and compassion, anger and fear. Of course, an AI may string together words like, “I feel angry,” but that’s just because it’s seen examples of those words being strung together previously, where those examples come from sentient, conscious human beings who say things like, “I feel angry” when they feel angry. (Actually they mostly say things like “fuck you!” when they’re angry, especially in New York, but you get the point). This is one reason why we should continue to roll our eyes at Blaise Lemoine’s claim that LaMDA is sentient. There is absolutely zero reason to think AI is sentient.

The second point drives a wedge between intelligence, on the one hand, and motivation or desire, on the other.

Here’s a standard way to think about the mind (or animal, including human, psychology) that has stood for centuries: our intellect provides us a map of the world while desire points us in a direction.

The store is down the street. To become a lawyer, go to law school and pass the bar. If you go outside now you’ll get soaked in the storm. And so on. Those sorts of things are part of our map of the world. But maps don’t tell you where to go. The map doesn’t tell you to go to the store or to become a lawyer or whether to go outside. Your desires are what set the destination.

If you want a snack or to be a lawyer or you don’t want to get wet, then all else equal you’ll go to the store, become a lawyer, and either choose to stay inside or bring an umbrella. The distinction between intelligence or knowledge, on the one hand, and motivation or desire, on the other, is crucial for understanding that even if AI is intelligent it does not desire anything.

That means it doesn’t desire the destruction of humankind. It also doesn’t desire the flourishing of humankind. It doesn’t desire for the patient to be healed or to further suffer. It neither holds mere mortals in contempt nor exalts them as gods. It is utterly apathetic, incapable of feeling or desire or preference or joy or sorrow or anything in the vicinity. (This is not to say that AIs cannot have a goal that is given to them by a person; more on this in Chapter 2).

This is one reason people can calm down about AI and the destruction of humanity. Even if you think AI is intelligent, it just doesn’t want anything. Evil intent is not on the table for things we need to worry about.

So, at most, we have a mind, an intellect, that is devoid of feeling sensations or emotions and wants for nothing. This is considerably less scary than the Terminator. (It is also unembodied, though researchers are working on integrating AI with robots).

Now that we’ve whittled this thing down to a mere intellect, let’s assess whether it’s even that, as the technologists have claimed.

Thermostats and Nipples

How can we determine whether software that learns by example is intelligent? I’m not going to tell you it’s literally impossible that is intelligent. That’s too high a bar. But I’m going to give you strong reasons for being deeply skeptical. To do that, we’ll take three steps.

Step 1: I’ll give you an example of something that acts intelligently but we all know it isn’t intelligent.

Step 2: I’ll explain what’s missing in that thing that leads us to say, “that thing is not intelligent.”

Step 3: I’ll show you that the missing thing is also missing in AI.

This is all fairly abstract, but don’t worry, all will become clear with an example or two. Now let’s get those steps in.

Step 1: Your thermostat has sensors that indicate when the temperature reaches below 68 degrees Fahrenheit. When the temperature hits 67, the thermostat does what a person might do – it turns the heat on. Put differently, it behaves as an intelligent person would (if the person doesn’t want to be cold). But of course no one thinks thermostats are intelligent. Yes, they are “sensitive to” the temperature, but then again, so are nipples, and no one thinks nipples are intelligent entities.

Step 2: What’s missing from thermostats? What don’t they have that makes it the case that they aren’t intelligent? In a word: understanding. Thermostats don’t understand the world. They don’t have a grip on what the world is like. They don’t understand the meaning of “cold” or “hot” or “temperature” or “degrees.” It receives certain inputs from its sensors and regulates temperature in relation to a goal of keeping people not too hot and not too cold without understanding anything at all.

You might want to ask, “well what’s understanding?” That’s a fair question, but we’re going to put it to the side. I think you know perfectly well that thermostats and nipples don’t understand anything. I think you also know that you understand all sorts of things; you understand that 2+2=4, you understand that the expression on her face indicates that she’s happy, you understand that and how you made a mistake, and so on. In other words, you understand “understanding” well enough to know that you and other people understand things and thermostats don’t.

Step 3: Now we come to the hard part. We need to show that understanding is also lacking in software that learns by example. How can we do that? Well, we show ways in which AI is sensitive to the outside world that mirrors a human acting intelligently but we don’t think it understands anything (just like the thermostat). As it happens, there’s a famous thought experiment that purports to demonstrate exactly that.

Do You Understand Chinese?

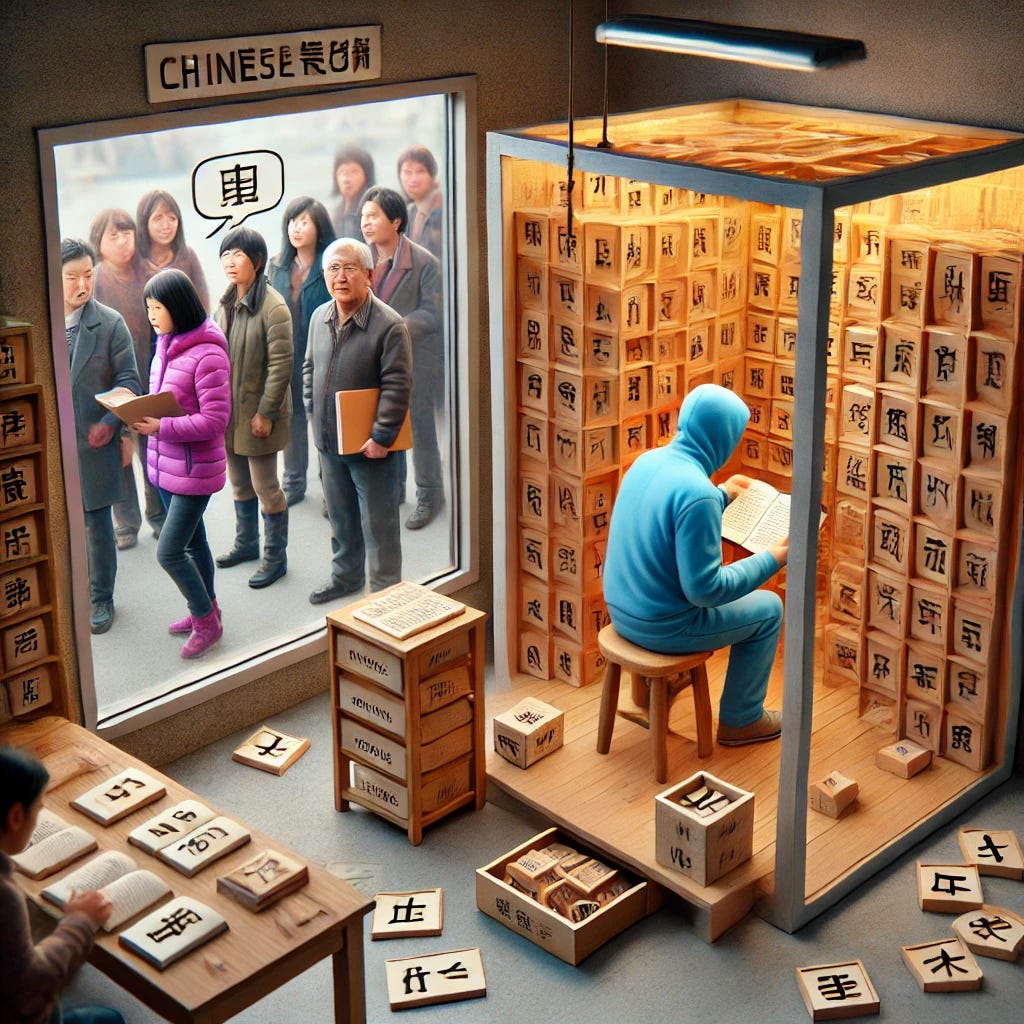

The famous thought experiment was brilliantly concocted by philosopher John Searle. It’s now called “the Chinese room argument.” It goes like this.

Suppose you’re in a room and at the door in the room there’s a little mail slot. And there’s someone on the other side of the door who passes messages to you, only they’re in Chinese. You (let us suppose) don’t speak Chinese. You don’t understand the symbols that are on those messages. But you do have in the room with you a big rule book, and you can look up the symbols that were passed to you in this book. The book doesn’t contain any English words, but it tells you that if you receive a message with a bunch of symbols that look like this, then you should write these symbols on a piece of paper and pass it back through the mail slot.

You do this for a little while. You receive the Chinese message, look up those symbols in your rule book, do your best to write the symbols the book tells you to write on a piece of paper, and then pass that message back through the mail slot. And on and on, back and forth.

Here’s the catch. The person outside the door thinks she’s having a conversation with a fluent Chinese speaker. She put something like “Hi, how are you?” into the mail slot and a bit later she gets a message back that says, “I’m well, how are you?”. The conversation keeps going back and forth like this, reenforcing her belief that she’s talking to someone who understands Chinese.

But a question! Do you, sitting in that room with your rule book, understand Chinese?

Of course you don’t. With your rule book you’ve learned to act in ways that make someone think you understand Chinese, but in fact you do not. You’re a lot like your thermostat. You’re sensitive to the world outside you and react to it in ways that might reflect there’s understanding going on, but there isn’t.

The Chinese Room argument teaches us two lessons.

Lesson #1: There’s a difference between a thing that understands, on the one hand, and something that is capable of deceiving others into thinking it’s something that understands, on the other. The Chinese speaker on the other side of the door understands Chinese and you (unintentionally) deceived her into thinking you’re a thing (or rather, a person) that understands Chinese.

Lesson #2: Understanding a language is more than just being able to manipulate symbols according to rules that create the impression of understanding.

Returning to the Steps

In step 1, we saw that thermostats behave “intelligently” but aren’t intelligent. In step 2, we saw that thermostats lack understanding. And now in step 3, we’ve seen an example of something that can interact with language speakers according to various rules but there’s no understanding. And the upshot, of course, is that this is exactly what AI of the ChatGPT variety does.

Text generating AI learns how to put words together coherently from seeing lots of words that are put together coherently. It does this, roughly, by learning “rules” for how words go together. To simplify the matter a great deal, you can think of rules looking like this: “If the message received includes words like ‘mother’, ‘loss’, and ‘grief’ grouped together, then reply with words like ‘sorry’ and ‘I’m’ and ‘difficult’.” That, or something like that, is the rule the software learned after seeing lots and lots of examples.

To the unsuspecting person, it will certainly appear the software understands how difficult it is to lose one’s mother and that it’s helpful to say to people who are grieving that you’re sorry for their loss. But, just like you don’t understand Chinese by virtue of moving symbols around according to your rule book, the software doesn’t understand English by virtue of moving symbols around according to its rule book.

The Chinese Room argument is very powerful. That said, I do not want to pretend that it’s without its detractors. Indeed, there is no substantive philosophical claim that gets made by a philosopher, especially a famous one (in the small circle that is academic philosophy, anyway) that is not vociferously and powerfully attacked by other philosophers. So I do not want you to conclude that the Chinese room argument is definitely sound and so software that learns by example is definitely, without even the tiniest fraction of doubt, guaranteed by God, not intelligent. Rather, what I think we ought to conclude is that we should regard anyone who proclaims something like “we have software that is intelligent, that understands the world,” deserves to be looked at with a highly arched eyebrow. Our skepticism of their claim is justified. Rolling eyes and laughing may also be called for.

The Technologists Go on the Attack

The technologists might complain that I’m being unfair. That I haven’t given them their day in court. After all, I presented reasons for thinking we should be deeply skeptical of their claims to intelligence without letting them have their say for why we should think we have intelligence. And to this I say, ok, let’s see what you got.

There are two influential ways of arguing that software that learns by example is intelligent.

No AI Left Behind: Test, Test, Test

The first is to think of AGI as intelligent if it can pass various tests. What kinds of tests? Well, the kinds of tests we use on humans to test their intellectual mastery of the law, medicine, or accounting, for example. Or we can concoct other kinds of tests, as the team at Microsoft did, to determine whether and to what extent it can do something novel, like writing a mathematical proof in the style of Shakespeare. And as it turns out, ChatGPT-4, the latest from OpenAI, can do quite well on these tests. It scored in the 90th percentile on the bar exam and 93rd percentile on the SAT Reading and Writing section. (It also failed at high school math, but for what it’s worth, I recently asked a college grad working at my climbing gym what 32x10 is and he couldn’t do it. I find this far more terrifying than AI).

But this method of testing for intelligence is a non-starter. And we know this because the Chinese Room argument gave us lesson #1: there’s a difference between being intelligent and being such that something can deceive people into thinking its intelligent. This shows us that a really good deceiver would pass lots of tests. In fact, that’s precisely what its deception consists in! And a perfect deceiver would deceive perfectly (never making any mistakes or saying or doing anything that would cause skepticism in its audience).

So I don’t care how many tests you throw at this thing and how well it performs; it’s just not relevant to assessing whether it possesses understanding.

You Say “Tomato,” I Say “Tomahto,” “You Say Mind, I Say Computer”

The second kind of argument technologists like to offer has less to do with software that learns by example as such and more to do with how they think about the human mind. More specifically, they like to compare our minds to computers and extrapolate from there that we can make better - that is smarter and faster - computers.

According to this picture, the human brain is the hardware and neurons firing is the software performing calculations. Our minds are, they say, computers; they’re information processing units. And then the technologist gets really excited:

“If the human mind is intelligent and that’s because it’s an information processor, and it’s an information processor because of hardware and software, well, we can build that!

And then in a fit of nerd excitement fueled by too much Star Trek:

“…And once we create one intelligence that can process information faster than us we can tell it to figure out how to make a more intelligent thing! And it’ll do that and then we can tell that new superintelligence to create something of even more intelligence. And then we can ask that super-duper intelligence to create….”

At this point the technologist usually red lines and they need smelling salts to be revived. But, as you suspected, there’s good reason to doubt all this.

It’s true that humans are intelligent (with the exception of the climbing gym employee) and it’s true that humans have brains and neurons that fire, and it’s true that those things are part of the picture of what makes up the human mind. But is it everything?

Philosopher and cognitive scientist Eric Mandelbaum points out that’s certainly not the case. We know our minds are affected by things other than neural firings. For instance, we know various neurochemicals (e.g. serotonin and dopamine) and hormones (e.g. testosterone and estrogen) influence our psychological states. In fact, for all we know about how our minds work (and we really know very little), sub-atomic particles that make up the brain influence how our neurons and minds work. What’s more, for all we know, those neurochemicals and/or hormones might be absolutely necessary for both the consciousness/sentience that alludes AI and for neurons to fire as they do. But none of these things – neurochemicals, hormones, subatomic particles - are well accounted for on the “the mind is a computer” picture.

“Very well,” our technologist might say. “I’ll concede all that. But don’t go around chanting “Mandelbaum! Mandelbaum!” too quickly. I don’t care about consciousness and sentience anyway. All I care about is the information processing part and that’s the neurons firing.”

But do we know that the neurons fire as they do without the chemicals? Can we have neurons firing in just the way they are after having drained the brain of all neurochemicals and hormones? Would we then be bereft of desire? Can we have a brain with all the beliefs/intellect/understanding and no desires?

I don’t know the answer to these claims (although I confess to seriously doubting our intellects would be intact if we sucked out the neurochemicals). But nor do the technologists. Nor does anyone, I suspect. And that means that the “the mind is just a computer” path is not a great one to go down if you’re in the business of vindicating the claim that a piece of software (that learns by example) is intelligent.

One last point on this.

Let’s grant, for the sake of argument, that technologists really could figure out how to create a machine as intelligent as humans. As we saw above, technologists then love to extrapolate: “If you have an intelligent AI then it could endlessly improve itself” or “If you have 2 or more intelligent AIs then they could endlessly improve themselves.” But how would they know that? Sure, maybe that would happen. Maybe it wouldn’t. Maybe they would plateau earlier than anticipated. How could we know in advance of running that program? Again, it’s possible, but possibility is cheap. It’s possible that in five minutes a bird is going to fly into the window you’re closest to right now, but there’s no evidence for that. It’s possible an artificial middling intelligence would endlessly iterate on itself until it creates a superintelligence, but there’s no evidence for that, either.

A Fair Low Blow

I think there are very powerful reasons to be skeptical that software that learns by example is intelligent. The Chinese Room argument, the irrelevance of their tests, the dubious claim that the human mind is just a different kind of computer – all of this is the tip of the iceberg of evidence against the technologists (there’s a lot more philosophy to dig into). But I can’t resist – ok, let’s face it, I don’t even want to resist – making an observation that should cast more doubt on the technologists.

They want software that learns by example, which they brazenly call “artificial intelligence,” to be intelligent. First, it would be straight up amazing and incredible if they actually created another intelligence. It would be one of the most amazing intellectual feats in human history. Of course they want to achieve that. Second, and relatedly, think of how much ego is involved in that desire. To be the creators of another intelligence. To be the coolest kids on the Silicon Valley block. Indeed, to be gods! Surely this is tempting. And third, the financial incentives to see things this way is alluring. We’re talking about billions of dollars being poured into AI, much of which ends up in their pockets. This is all just to say that the technologists are intellectually compromised; it would be shocking if they could be completely objective in their assessment. Not every single one, of course. Blaise just seems like a really bad judge of non-character. But a lot.

Where Are We on the Whole “AI Will Kill Us All” Front?

If AI is going to lead to the extinction or subjugation of humanity, it will not be by virtue of software that learns by example being sentient, desirous, or intelligent. But while I’ve spent this chapter taking the winds out of the sails of technologists who eagerly await their new god, the truth is that software that learns by example can also be very powerful. Put differently, while all those tests that it impressively passes doesn’t show the software is intelligent, it does show that it can be extraordinarily useful.

This utility itself may present existential concerns of a different variety. What if, for example, AI is embedded in nuclear weaponry and then it goes sideways and, yada yada yada, we’re all dead? Or what if, to take Nick Bostrom’s famous example, we tell it to maximize the production of paperclips and it realizes the metal in the human blood stream could be used to make paperclips and once again, yada yada yada, we’re all dead?

I don’t think these kinds of scenarios are literally impossible. But there’s a whole lot going on in those yada yada yadas. The path from developing AI that is involved in nuclear weaponry to testing it to getting it approved, etc. is a very long and complicated path containing hundreds of steps along the way. It’s possible every one of those steps will be taken, but as I noted earlier, the fact that something is possible doesn’t entail that there’s any evidence for it. This leaves the catastrophist in the position of having to argue that, not only is the sky possibly falling, but that it’s sufficiently probable such that we need to spent time, money, attention, and social and political capital addressing it instead of spending it on, for instance, the well documented existential threats associated with climate change. I have yet to see anyone give any argument that even vaguely accomplishes that goal.

Get Riled Up About the Right Sorts of Things

None of this is to say that AI doesn’t pose very real risks. They’re just not existential risks. And if we’re going to address the real risks – discriminatory or biased AI, privacy violations, reduction of autonomy, and son on - let’s not stumble out of the starting blocks by tripping on the fancy words and big, scary claims offered to us my ego and economically motivated technologists don’t even know that philosophers have been working on this issue for centuries.

If you like this article, you’ll probably like my podcast, Ethical Machines.

What about his core point that bots and pernicious algorithms, irrespective of their provenance, amplifying emotions such as fear, hate and divisions and amplifying defamatory lies need to be regulated?